Hacking the Finder with lldb and Hopper

Do you want to never press Show Package Contents again? Or maybe you just want to learn a couple of practical lldb techniques? Either way, I invite you on the journey to discover a hidden feature within the Finder!

In this article I will be using:

- Hopper disassembler

- Multiple lldb features

- Opcode manipulation to change a program behavior

I hope you will learn something new!

The backstory

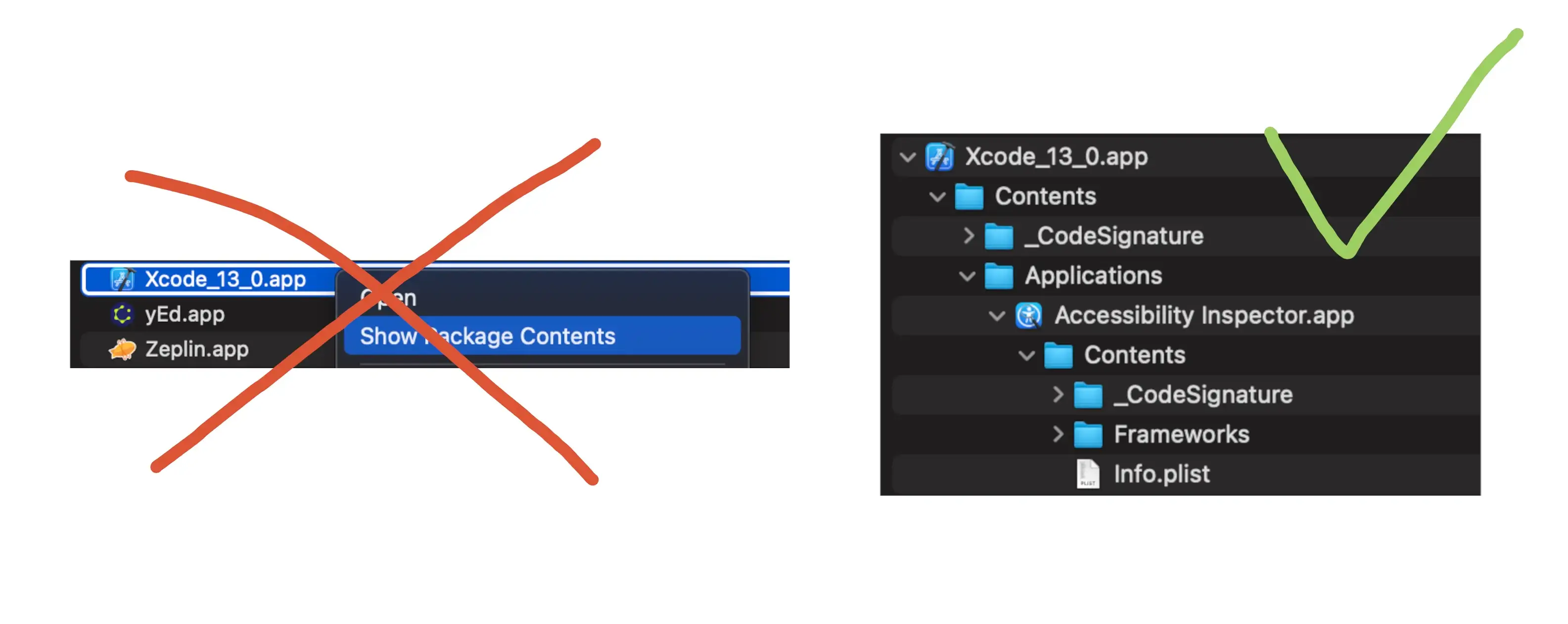

Recently I had to work a lot with packages. What kind of packages? The most usual example of a package is an .app bundle, for example, the Xcode.app:

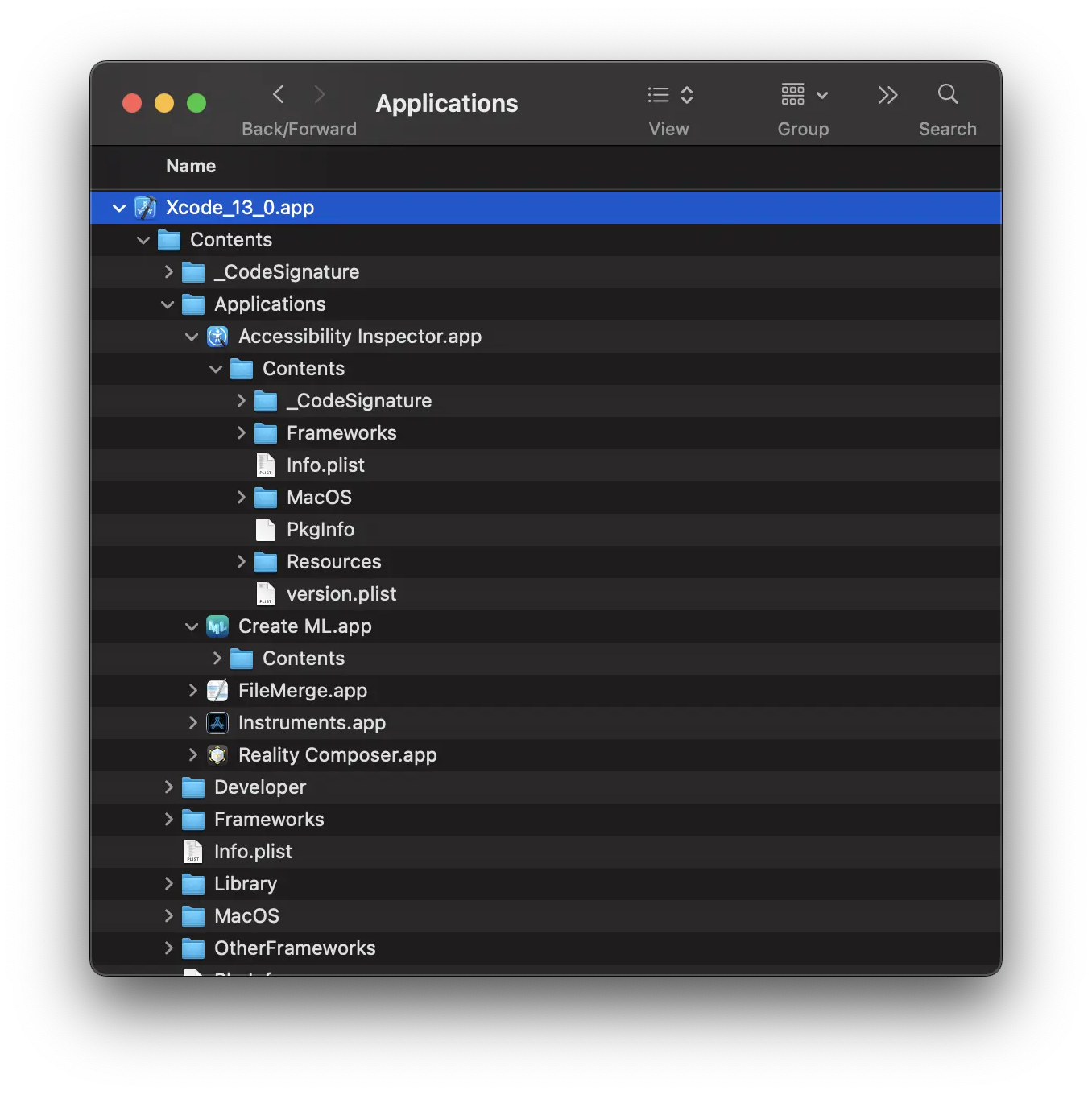

Imagine you are working on an .app with multiple .bundle and .appex directories inside it. If you want to inspect the contents of this hierarchy, you would normally use a Finder. You build using Xcode, go to the DerivedData/Build/Products, and… unfortunately, to view the contents of each package you have to click through Show Package Contents. This is inconvenient because Finder doesn’t allow you to easily walk in and out of the package and working with multiple packages simultaneously easily gives you vertigo.

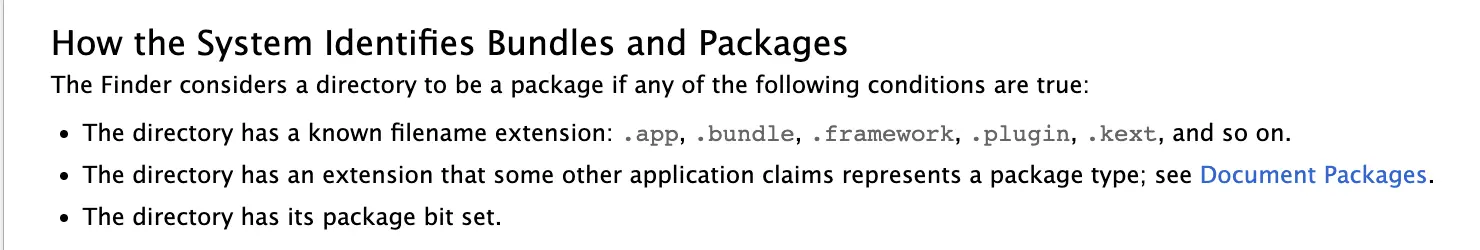

But what if it was possible to view packages as regular directories? After all, package is just a regular directory. How does Finder even understand something is a package? It turns out some file extensions such as .app are hardcoded in LaunchServices to be recognized as packages. For example, if you simply create a directory:

$ mkdir Example.app

it will show up as a package in the Finder.

You can also register your own file extensions as packages:

Reverse engineering Finder using Hopper

Hopper is a great tool to learn about how a program works. Hopper’s basic utility is a binary disassembly tool but it also has many features which can give you a better insight into how a program operates. For example, it can turn assembly back into a pseudo-code which is often much easier to reason about than an assembly.

Let’s start by opening the Finder in Hopper and seeing if we can spot something of interest:

$ hopperv4 --executable /System/Library/CoreServices/Finder.app/Contents/MacOS/Finder

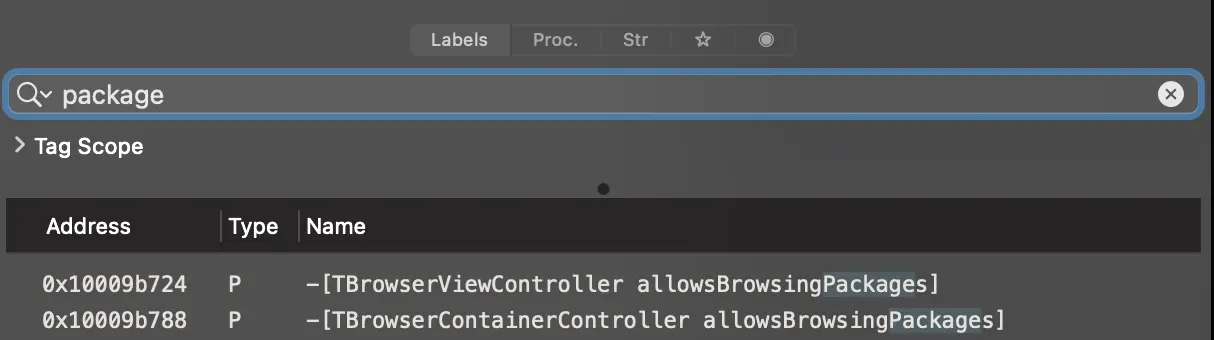

Now we can search for references to “packages”:

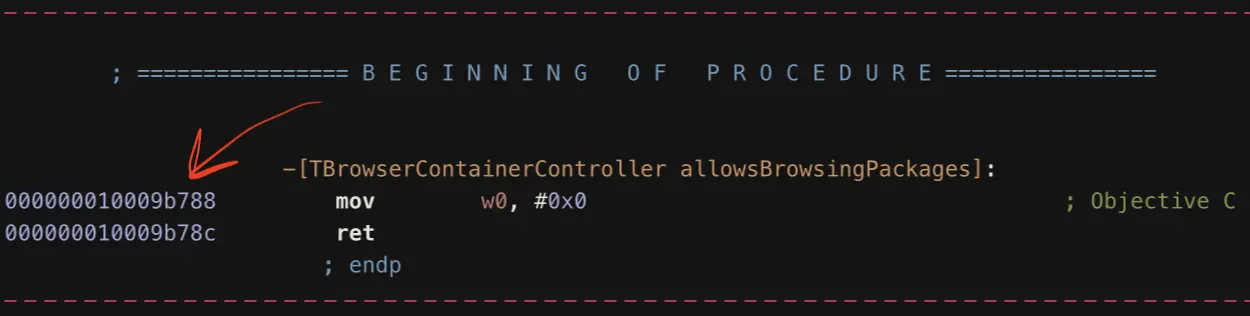

And thankfully there are some! Of particular interest to us is the procedure lurking under the symbol -[TBrowserContainerController allowsBrowsingPackages]. If we look at the pseudo-code there is something weird about this procedure:

int -[TBrowserContainerController allowsBrowsingPackages]() {

return 0x0;

}

It seems that this is a method that returns a boolean flag but it always returns false. Why could that be? Most probably when Finder is compiled for internal testing at Apple, this method comes with some logic inside but for release build this logic is removed.

So what happens if we flip the output of this method to return 1 (i.e. true)? Let’s use lldb to find out. Inconveniently Finder is protected by SIP, so to attach to Finder you will have to disable it. After SIP is disabled, connect to Finder with lldb:

$ sudo lldb --attach-name Finder

The procedure that we are interested in starts at address 0x10009b788 (in different MacOS versions it might be different):

Let’s set a breakpoint there:

(lldb) breakpoint set --shlib Finder --address 0x10009b788

Breakpoint 1: where = Finder`___lldb_unnamed_symbol2354$$Finder, address = 0x0000000102f83788

Notice that the address 0x0000000102f83788 that the lldb outputs is different from the one we specified with --address due to ASLR. This is the actual slid address where the procedure is loaded and it will be different every time the Finder process is launched. Remember this address because it will be useful to us later.

Now click on /Applications in the Finder and it should freeze due to a breakpoint being hit in lldb. So how do we return true instead of false? Lldb has just the command for returning early from a call - thread return. Let’s use it returning 1 instead of 0:

(lldb) thread return 1

(lldb) continue

(you will have to repeat that for every package in the folder or breakpoint disable)

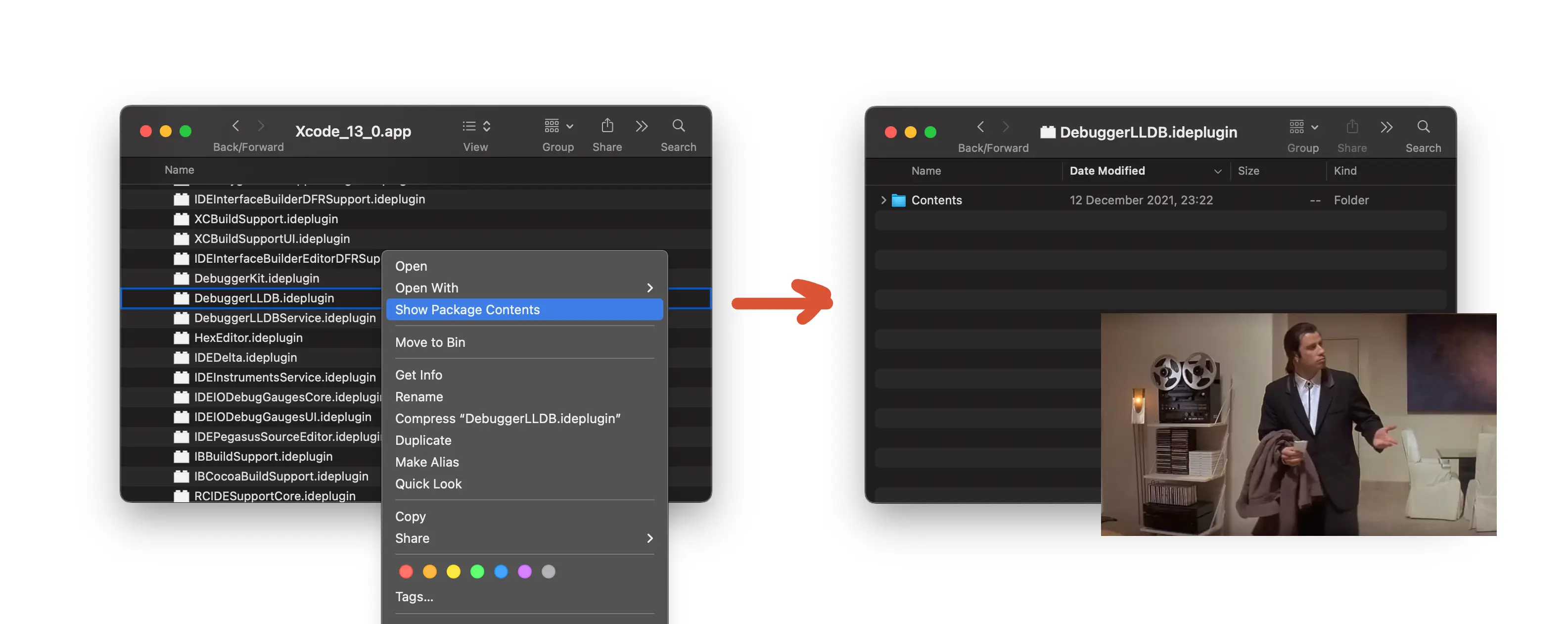

After the Finder execution continues you should finally be able to browse through any package as if it was a regular directory:

So after all the -[TBrowserContainerController allowsBrowsingPackages] is indeed responsible for displaying packages as regular directories! But how can we return 1 from this procedure without having to type commands in lldb after opening each directory in Finder?

Solutions that don’t work

Unfortunately simply scripting the breakpoint using --command 'thread return 1' and --auto-continue True crashes Finder for some reason and it would probably impede Finder’s performance. Before macOS 12 a fine solution using swizzling worked perfectly:

(lldb) expression --language swift --

Enter expressions, then terminate with an empty line to evaluate:

1: import Foundation

2:

3: extension NSObject {

4: @objc func swizzled_allowsBrowsingPackages() -> Bool { return true }

5: }

6:

7: guard let originalMethod = class_getInstanceMethod(

8: NSClassFromString("TBrowserContainerController"),

9: Selector("allowsBrowsingPackages")

10: ), let swizzledMethod = class_getInstanceMethod(

11: NSObject.self,

12: Selector("swizzled_allowsBrowsingPackages")

13: ) else { return }

14:

15: method_exchangeImplementations(originalMethod, swizzledMethod)

However, it also crashes at method_exchangeImplementations starting with Monterey.

That leaves us with the last reserve tool…

Manipulating opcodes

Underneath, the code that the CPU executes is just a sequence of numbers and those numbers can be manipulated. Let’s use memory read to make sense of the ARM64 assembly and the underlying opcodes. We will need the slid address of the procedure that the lldb gave us when we set the breakpoint (use breakpoint list to see previously set breakpoints):

(lldb) memory read --format instruction 0x0000000102acf788

0x102acf788: 0x52800000 mov w0, #0x0

0x102acf78c: 0xd65f03c0 ret

We can see that mov w0, #0x0 is responsible for setting the output of the allowsBrowsingPackages method. So what would it take to turn #0x0 into #0x1? To figure out we can disassemble a similar function:

$ echo 'int foo() { return 0; }' | clang -c -xc -o /dev/stdout - | objdump -d /dev/stdin

the most important output here is the following sequence of bytes:

0: 00 00 80 52 mov w0, #0

4: c0 03 5f d6 ret

notice the output of objdump matches the disassembly from lldb perfectly, the only difference being that the disassembly from lldb is reversed due to endianness. Now, what happens if return 0 is changed to return 1? We get the following disassembly:

0: 20 00 80 52 mov w0, #1

4: c0 03 5f d6 ret

The difference is that the first byte changed from 0x00 to 0x20.

Now we can change the same byte in the Finder process and see what happens:

(lldb) memory write 0x0000000102acf788 0x20

and if we read the instructions now, the assembly should change as expected:

(lldb) memory read --format instruction 0x0000000102acf788

0x102acf788: 0x52800020 mov w0, #0x1

0x102acf78c: 0xd65f03c0 ret

Now we can finally unpause the Finder using continue.

Yay! We can now browse any package in the Finder without having to Show Package Contents every time (who cares about SIP anyways).

In the future episodes...

While automating this solution I also had a chance to write some lldb python scripts and debug those scripts in PyCharm. In the next articles, I hope to cover those techniques as well.

Did you find any of the techniques used in this article useful? Do you have any questions or suggestions? Please let me know in the comments!